Six years later in Russia, on 8 March 1917, textile workers demonstrated, calling for ‘bread and peace’, a demand that would mark the beginning of the second Russian Revolution. It prompted Leo Trotsky to write, ‘23 February (8th March) was International Woman's Day and meetings and actions were foreseen. But we did not imagine that this 'Women's Day' would inaugurate the revolution. Revolutionary actions were foreseen but without a date.’ One week later, the Tsar Nicholas II abdicated, and women were granted the vote (it would be another eleven years before women were given the same right – to vote on equal terms with men – in the UK).

If, today, the international celebration is intended to commemorate women’s achievement and mark the strides forward we’ve made towards equality, its revolutionary origins are still very much in evidence. Sadly, they have to be; despite all the change for the good, there is still some way to go.

This year’s campaign theme is Break The Bias. As its organisers say, ‘Imagine a gender equal world. A world free of bias, stereotypes, and discrimination. A world that is diverse, equitable, and inclusive. A world where difference is valued and celebrated. Together we can forge women's equality. Collectively we can all #BreakTheBias.’

And, to attest to the power of individual efforts to affect collective change, we celebrate some of the great women who have, indeed, transformed the world.

Happy International Women’s Day 2022.

Mary Seacole

Mary Seacole (neé Grant) was born in Jamaica in 1805. As a mixed-race woman, born to a Jamaican mother, who kept a boarding house for injured soldiers, and a Scottish father, her civil liberties were drastically curtailed. And yet that did not stop her travelling extensively through the Caribbean, Central America and Britain, supplementing her working knowledge of medicine by learning about new European approaches. When she approached the War Office in England with a request to be sent to the Crimea to help fallen soldiers, her offer was refused.

Indefatigable, she refused to take no for an answer, instead funding her own trip; upon arrival, she promptly set up the British Hotel to provide a ‘mess-table and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers', as well as visiting the battlefield – sometimes under fire – to tend to the wounded. When she finally returned to England, she had few means and was in poor health. The press, however, reported her good deeds and later her plight; duly, a festival was held to raise money in thanks for her pioneering war effort in the face of the dual discrimination of gender and race.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Florence Nightingale

Another inspiring woman, another nurse. Florence Nightingale – otherwise known as The Lady With the Lamp – was born in Italy to affluent British parents in 1820. Her ambition to become a nurse took hold as a teenager, when she would minister to ailing people from the village next to her family’s estate. And yet her social stature dictated that rather than follow a profession, she should marry a man of means. Forbidden to pursue nursing, she nonetheless ignored her parents’ wishes; moved to London in 1850; and took up a post at Middlesex Hospital.

There she rose quickly and, when there was an outbreak of cholera, she championed improved sanitary measures to stop its spread. That practice would stand her in excellent stead for her next challenge: as a nurse in the Crimea. In 1954, Secretary of War Sidney Herbert wrote to commission her to gather together a corps of nurses to tend fallen and sick soldiers. When she arrived, she saw that unhygienic conditions were causing more men to die of illness than of their wounds. She rallied the 34 nurses under her care, as well as the more physically able of the soldiers to clean the place up, and ministered to patients throughout the night. Later, with the support of Queen Victoria, she helped create a Royal Commission into the health of the army, where leading statisticians discovered that 16,000 of the 18,000 deaths were from preventable diseases—not battle. She established new standards of sanitation in the army and beyond, founded St Thomas’ hospital and revolutionised the way nursing was seen.

Henry Hering (1814-1893), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Marie Curie

Marie Curie was a Polish scientist and the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, a feat she achieved twice: jointly with her husband in 1903, and then later solo in 1911. Born in 1867, she made the ground-breaking discovery of radioactivity, as well as of two new chemical elements: polonium and radium. These discoveries were harnessed to develop X-rays – which not only were vital for use on the battlefield in WW1, but also remain a standard medical procedure today.

Henri Manuel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Emmeline Pankhurst

Where would we be without the huge sacrifices made by the suffragettes and suffragists? It’s extraordinary to think that less than a century ago, women could not vote on equal terms with men. Our thanks go up, then, to the politically radical Emmeline Pankhurst who, as early as 1889, founded the Women's Franchise League, its aim to secure the vote for married women in local elections. That, though, was just the start. Using violence – including arson and window smashing – as a means to draw attention to the cause, she was no stranger to the inside of a prison cell, while one of her fellow suffragettes, Emily Davison, was killed when she threw herself under the king's horse at the Derby in protest. She died in 1928, having lived just long enough to witness her campaigning bear fruit as women were finally granted the vote.

Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Coco Chanel

Walk down any of the world’s fancier shopping streets and you’re likely to see the interlocking Cs logo that signifies a Chanel store. But, as one of the most influential couturiers of the 20th-century, Coco Chanel did more for women than simply to create beautiful clothing. A milliner by training, she soon moved beyond the hat to deliver clothes that would be revolutionary. As she put it, ‘Nothing is more beautiful than freedom of the body.’ And with that mission statement, she set about making women feel just as comfortable in their clothes as men, popularising trousers and inventing the ‘little black dress.’ Et voila, with the introduction in the 1920s of her two-piece suit for women, she liberated half of the population from the restrictions of formal women’s wear and – gulp – corsetry.

Justine Picardie, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Irena Sendler

Tales of extraordinary bravery abound during the WW2 years. Yet one woman stands out as particularly extraordinary. A Polish humanitarian, social worker and nurse, she served in the Polish Resistance and headed up the Zegota, the country council to aid Jews. As one of a network of female workers, she helped to smuggle Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto, providing them with both counterfeit ID documents and shelter. By 1943, the Gestapo suspected her activity; duly, they imprisoned and tortured her; even under such duress she refused to reveal the whereabouts of the children she had rescued. She was sentenced to death, but narrowly escaped on the day. Her extraordinary efforts have been written about in various biographies and history book and, in 2009, a TV film about her was released, entitled The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mary Wollstonecraft

Writer, philosopher and advocate of women’s rights, Mary Wollstonecraft, born in 1759, was decades if not centuries ahead of her time. During her lifetime, her unconventional personal life sadly overshadowed her work. Today, thankfully, she is remembered instead for her work, which included the seminal A Vindication Of The Rights Of Woman (1792), in which she argued that lack of education was the only barrier to male and female equality. She wrote, ‘For the improvement must be mutual, or the injustice which one half of the human race are obliged to submit to, retorting on their oppressors, the virtue of men will be worm-eaten by the insect whom he keeps under his feet.’

John Opie, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ada Lovelace

Ada Lovelace, neé Augusta Ada Byron, Lady Byron, shares two things with her absent father, the romantic poet Lord Byron: an untimely death at the age of just 36; and a legitimate claim to genius. Getting on for two centuries after her death in 1852, her exceptional work still influences our daily lives; as the first ever computer programmer, her pioneering efforts to write a program for her associate, mathematician Charles Babbage’s prototype computer, represented a staggering step forward into the digital age.

Margaret Sarah Carpenter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Jane Goodall

When Jane Goodall ventured into the forests of what is now Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania, she had no formal training. What she had in spades, however, was passion and steely resolve to observe chimpanzees in the wild. Her discoveries about their behaviour challenged conventional scientific belief: that they can make and use tools, and that their social structures and interactions are far more complex than had ever been imagined before. Today Jane is still hard at work, raising money and awareness of the necessity to protect chimpanzee habitats through her non-profit organisation, the Jane Goodall Institute.

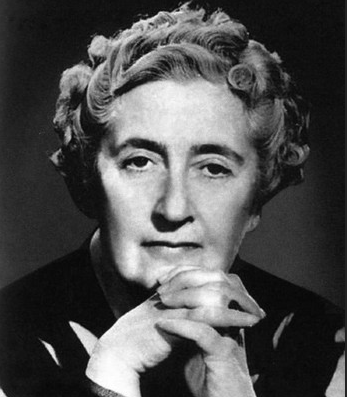

Agatha Christie

All hail Agatha Christie, the best-selling novelist of all time. As prolific as she was imaginative, Christie is best known for her 66 novels and the creation of not one but two legendary detectives: Miss Marple and Hercules Poirot, who are still much adored and much adapted, 46 years after their creator’s death. In addition, there were also fourteen plays – one of which, The Mousetrap, is the longest-running in history, having been on continuously from its inaugural performance in 1952 until 2020, when Covid forced theatres to close. Although exceptionally well-travelled in later life, her creativity was in evidence from the age of five, when she taught herself to read and spent the ensuing years absorbing other worlds and others’ words.

Agatha Christie plaque -Torre Abbey.jpg: Violetrigaderivative work: F l a n k e r, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Nellie Bly

T’was a time when women journalists were typically confined to writing about polite matters, such as dresses and society affairs. Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922) refused to be hemmed in by such limiting parameters. Instead, she channelled her efforts into investigative journalism, exposing the injustices of society and shining a spotlight on the poor and oppressed. Most famously, she infiltrated New York’s Women’s Lunatic Asylum to research her book, Ten Days In A Mad House. Not content, however, with such feats, she also broke a world record by following in the footsteps of Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, and doing it just 72. An astonishing woman.

H. J. Myers, photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Amelia Earhart

The American aviator was the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean, and the first person ever to fly solo from Hawaii to the U.S. mainland. Born in 1897, she flouted the gender norms of the day, attending college and playing basketball. It was, however, while serving as a nurse’s aid in the Red Cross during WW1 that she was able to watch the Royal Flying Corps training in Toronto for the first time. She took her first plane ride in 1920 – and after that, she was smitten. She passed her flight test in December 1921, earning a National Aeronautics Association license. From there, she set new aviation records – including becoming the first woman to fly solo above 14,000 feet and making the first solo, nonstop flight across the United States by a woman. In 1937, on her second attempt to circumnavigate the globe, she went missing; her disappearance remains one of the great mysteries of the 20th-century.

NASA on The Commons, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

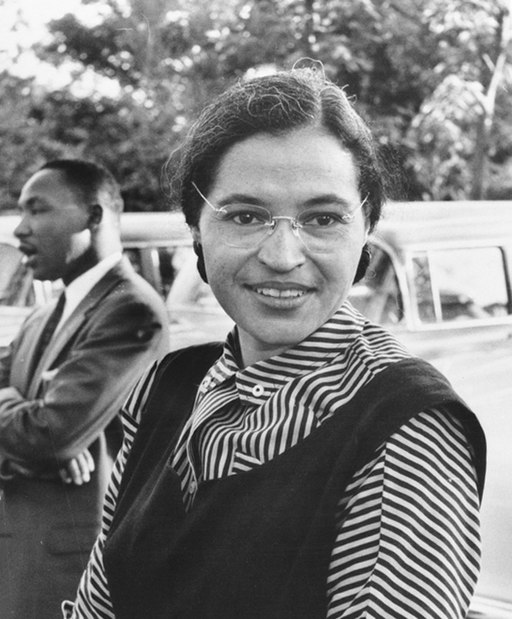

Rosa Parks

Rosa Parks helped to kick-start the Civil Rights movement in the US when she refused to give up her seat on the bus in Alabama in 1955. This dignified act of defiance and strength would prove a catalyst for the year-long Montgomery Bus Boycott, led by Rev Dr Martin Luther King Jr, which ended when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional. It wasn’t the first time Parks had refused to re-board the bus at the back after paying her fare; previously she had had an altercation with the driver, which ended in her getting off altogether, rather than ride at the back. However, this time, it changed history. In 1999, Parks was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honour that can be bestowed upon a civilian in America.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By Nancy Alsop

February 2022

Read More

10 Feminist Books That Changed The World

Six of the Best Feminist Podcasts

7 Body Positive Instagram Feeds to Follow